PHILADELPHIA — Darrell Brokenborough opened the bright yellow refrigerator that stood on the sidewalk outside a row home at 308 N. 39th St., smiled and said, “It’s full.” He balanced on his cane so he could take a closer look at the apples, yogurt, greens, pasta, cheese and chicken inside. On the front of the fridge was written: “Free food” and “Take what you need. Leave what you don’t.”

Brokenborough grabbed several bags of apple slices to slip in his slim over-the-shoulder bag. He tried to stuff some applesauce containers in his pouch, but returned the applesauce for someone else. His favorite groceries are fresh bagels and cream cheese, which weren’t there this time.

“I always recommend the fridge to my friends with kids. There’s always something healthy here,” he said, calling the free food he gets at the fridge on his way to and from a nearby medical facility a “blessing.”

Philadelphia now has more than 20 of these refrigerators sitting outside homes and restaurants, offering free food to anyone passing by. Volunteers keep the fridges clean and stocked with food donated from grocery stores, restaurants, local farmers and anyone with extra to share.

The concept of the community fridge ― sometimes called a “freedge” ― has been around for more than a decade, but it exploded during the pandemic as hunger spiked in the United States and worldwide. Images of thousands of cars lined up at U.S. food banks shocked the nation, and people looked for ways to help. There are now about 200 of these community fridges in the United States, according to the organizers of freedge.org, up from about 15 before the pandemic.

“There was a big focus on mutual aid in the past year in the U.S. as people were losing jobs. People wanted to bridge the gap between people who have food and people who don’t,” said Ernst Bertone Oehninger, who set up a freedge outside his Davis, Calif., home in 2014 and serves as a community organizer for freedge.org. “Community fridges won’t solve all the problems of food insecurity and food waste, but they help people connect, like community gardens.”

On a recent Tuesday, more than a dozen people visiting Philadelphia’s community fridges spoke to The Washington Post. Many praised the fridges for providing high-quality meat, vegetables and fruit that they would not be able to afford otherwise.

Terry Hare, 25, sat on a front stoop waiting for delivery of a new unemployment benefits card. He said the “community refrigerator” that appeared a few houses down from his last fall has been a lifesaver since he was laid off from his job at a UPS store early in the pandemic. It took weeks to get unemployment aid and longer to get food stamps. For a while, he lived off $175 a week, making it hard to get by, let alone buy fresh vegetables and meat.

“The fridge often has Whole Food meats and fresh stuff,” said Hare. “It’s a great resource for people of all different situations.” Hare is optimistic he will land work again soon, but knowing the fridge is there has provided extra comfort.

While the overall U.S. economy is on track for its best performance in almost 40 years, the rebound has yet to reach all neighborhoods. Business owners who host the fridges outside their workplaces say they see more people coming by now than they did last year.

“I’ve seen an increase in people coming to get food. The economy isn’t better in South Philadelphia,” said Vicky Borgia, a doctor who hosts the South Sixth Street fridge and pantry outside her medial practice. She pays the electric bill to run the fridge.

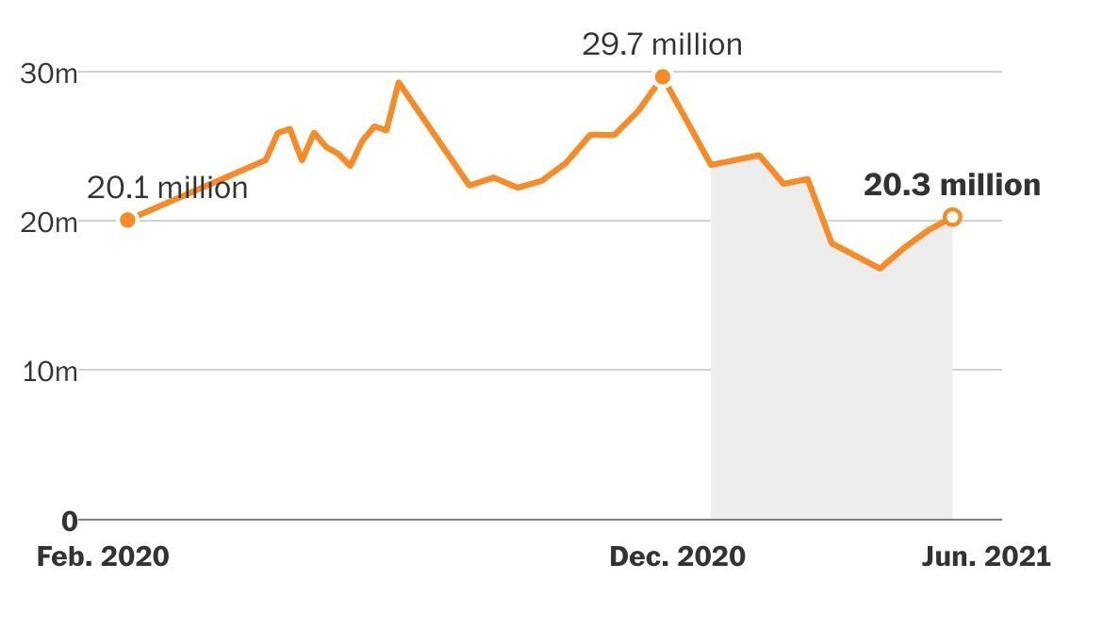

More than 20 million American adults still say they aren’t getting enough to eat, and another 42 million say they can’t always afford the types of food they want, according to the U.S. Census, which has tracked hunger throughout the pandemic. Rising prices, especially for popular food items like beef, milk and bacon, are putting additional strain on families.

Maria, a city social worker who spoke on the condition that her last name not be used because of the sensitivity of her job, dropped off some canned goods and hot dog buns to the bright blue refrigerator on South Sixth Street that has a cupboard next to it for dry goods. She was tempted by some gourmet cupcakes from a local bakery she saw in the fridge, but she ended up scooping a bag of carrots and some kale in her tote bag before she headed to her next appointment. “I’ve seen people who are hungry eat right out of the fridge,” Maria said. “I take what I can use and then give back. It’s a blessing.”

The share of Americans saying they “sometimes” or “often” do not have enough to eat was falling steadily this year, but progress began stalling in late April, worrying experts who had expected a further decline in hunger and are instead seeing numbers start to tick up again.

Certain groups still see alarmingly high hunger levels, including Black (15 percent) and Hispanic Americans (16 percent), Americans without a high school degree (24 percent), people whose employers closed temporarily (26 percent) or went out of business during the pandemic (33 percent), Americans earning less than $25,000 a year (24 percent), Americans serving in the National Guard or reserves (20 percent) and spouses of those serving in the National Guard or reserves (29 percent).

“There clearly are still lots of pockets of people that are facing real hardship,” said Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a professor at Northwestern University’s Institute for Policy Research. “The most recent hunger numbers ticked up a little bit. You start reading the tea leaves, which is all you can do right now, but it is making me nervous. We need the economy to take back off.”

Since Christmas, Congress passed two additional rounds of aid that extended unemployment help, bumped up food stamps and delivered more stimulus checks. The wider availability of vaccines has also made it safe to reopen many businesses, triggering over 9 million job openings for the unemployed.

Still, there are ongoing signs of need, especially in some parts of Philadelphia. At one point on a recent Tuesday, 10 people stopped by the community fridge outside of Borgia’s medical practice within an hour. Most walked away with one to three grocery items. Popular picks are kale, carrots, peanut butter and gallons of milk.

The concern is that now that the pandemic is fading, momentum for the community fridges could wane.

Some also see the refrigerators as a nuisance in certain Philadelphia neighborhoods. They can sometimes become a dumping ground for trash, and some fridges get smelly if they’re not cleaned out regularly. Each fridge in Philadelphia has a group of volunteers who maintain it and keep it stocked, but the high volume of traffic at some of the fridges has made it difficult to keep them clean at all times.

“I wipe the fridge down with bleach sometimes and try to help keep the trash organized,” said Thomas Gregg, who lives around the corner from the Philadelphia Community Fridge at 1229 S. Sixth St. “Sometimes it gets nasty, but I think they should keep it going. There is a lot of need here.”

At the fridge outside Borgia’s medical clinic, people have dumped chairs and other trash illegally. Someone stole the first fridge.

City inspectors who largely stopped patrolling for code enforcement violations during the pandemic are also starting to get more aggressive about the public refrigerators. The city has fined Borgia $50 several times for violating trash regulations. City officials say they are working on a set of guidelines for the free fridges, although they are not ready yet.

“We appreciate the many ways that Philadelphians look out for one another, especially to combat hunger and make food accessible,” said Sarah Peterson, a spokeswoman for Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney (D). She added, “From a health perspective, community fridges are not a city-sanctioned food distribution strategy. Unlike food establishments that the Office of Food Protection inspects, we cannot be sure of the provenance of the food, whether it has been properly stored, that it hasn’t been adulterated, and that the refrigerators are in good, working order and cleaned regularly.”

Despite some setbacks, Borgia and others said they are committed to keeping the free fridge effort going. Not only do they still see widespread need, but they have been heartened by how many people who live nearby have pitched in to help by cleaning or donating items.

“What we’re learning is when you do something like this, people will support it. People do have goodness and kindness, and they will bring food. People just didn’t even know the problems were so dire, especially for Philly,” said Michelle Nelson, founder of Mama-Tee.com, which now runs 18 bright yellow fridges in Philadelphia and has been inundated with requests to put more around the country.

Nelson said this is part of a movement known as “mutual aid,” where people, even those struggling, want to help each other and have a stake in the project — instead of just feeling like they are receiving handouts.

Howard Byrd, owner of Red’s Hoagies, has started putting extra sandwich meats and cheeses into the community fridge at 1901 S. Ninth St. that is across the street from his shop. Teachers from the nearby Southwark School say they bring leftover food boxes to the fridge now instead of throwing them away.

“I see a lot of people coming to the fridge. Food prices are going up. I’ve been trying not to raise my prices because people can’t afford it in this neighborhood,” Byrd said.

Whole Foods partnered with Nelson and her Mama-Tee fridges to supply some of the free food, including fresh sweet potatoes and collard greens, as well as lentils, which can go quickly in some neighborhoods. Nelson also just launched the first Mama-Tee grocery store in Philadelphia, which serves as both a free shop and a central distribution point to make it easier to restock the fridges.

Syona Arora, 28, lost her job at a museum at the start of the pandemic. Suddenly finding herself with a lot of free time, she began volunteering to deliver diapers, food and baby wipes to at-risk moms. But she wanted to do more. She heard about the community fridge initiative in New York City and was surprised to learn Philadelphia didn’t have anything like that yet. Arora and a few friends bought three fridges on Facebook Marketplace last summer and found places to put them in South Philadelphia, including outside Borgia’s medical practice.

Artists volunteered to paint the fridges with the Philadelphia Community Fridge logo, and local grocers and bakeries reached out to donate food. A friend with an herb garden on her roof has been packing basil and mint in plastic bags and putting it in the fridge.

“This is completely community-run. It’s possible,” said Arora. “It might only help a couple of families a day, but if everyone in community is doing this, you can help so many more people.”

"eat" - Google News

June 29, 2021 at 03:25AM

https://ift.tt/2Ta7x58

20 million Americans still don't have enough to eat. A grass-roots movement of free fridges aims to help. - Bennington Banner

"eat" - Google News

https://ift.tt/33WjFpI

https://ift.tt/2VWmZ3q

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "20 million Americans still don't have enough to eat. A grass-roots movement of free fridges aims to help. - Bennington Banner"

Post a Comment