It’s hard to imagine an America without potstickers and hot and sour soup. The now-ubiquitous Chinese staples were just two of the dishes that Cecilia Chiang, the monumental Bay Area restaurateur who died on Wednesday, is credited with popularizing in San Francisco and, in some cases, to the rest of the country.

When she opened San Francisco restaurant the Mandarin in 1959, she exposed locals to hundreds dishes from all over China and presented them with sophistication previously unseen in the city’s Chinese spots. After a few years, she moved the restaurant to Ghirardelli Square, where it grew into a 300-seat, elegant destination with wood-beamed ceilings and expensive chairs.

The Mandarin paved the way for modern, upscale Chinese restaurants, as well as any restaurant serving regional Chinese food, especially from Northern China, Sichuan and Hunan. And Chiang also greatly influenced the trajectory of Chinese-American food, with her son opening the chain P.F. Chang’s.

We sifted through The Chronicle’s archives to find eight Chinese dishes Chiang served at the Mandarin that eventually became fixtures of America’s Chinese food canon. With each one, see recommendations from Chronicle critic Soleil Ho for finding current versions.

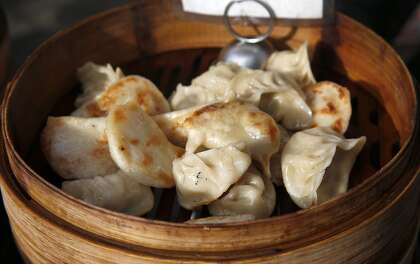

Guo tie: Now commonly referred to as potstickers, these crescent-shaped dumplings are pan-fried until they’re crispy on the bottom and juicy inside. They were on the Mandarin’s opening menu — five for $1 — and turned Chronicle legendary columnist Herb Caen into a fan of the restaurant. Chiang’s recipe for guo tie in her book “The Seventh Daughter” features the classic combination of Napa cabbage and pork, seasoned with ginger, green onions and sesame oil.

Where to find a great version now: For a classic pork potsticker likely similar to the ones served at the Mandarin, go to House of Pancakes (937 Taraval, San Francisco). Old Mandarin Islamic Restaurant (3132 Vicente St., San Francisco) makes delicious ones stuffed with spiced beef, and pop-up Good to Eat Dumplings (292 4th St., Oakland) offers a rectangular Taiwanese take.

Tea-smoked duck: One of the most famous dishes from the Mandarin is the classic Sichuan preparation of marinated duck smoked over tea leaves. The Mandarin’s version was rubbed with five-spice powder and beautifully bronzed, with a skin that “cracks like glass, leaving a gush of melting fat to bathe the rich meat,” according to former Chronicle critic Michael Bauer in 1988. A year earlier, former critic Patricia Unterman raved that the duck “distills the most poetically sensual aspects of Chinese cooking.”

Where to find a great version now: Z&Y Restaurant (655 Jackson St., San Francisco) is a reliable bet for most Sichuan dishes, and the crispy-skinned, tea-smoked duck is no exception.

Red-cooked pork: Chiang’s mother was from the Shanghai Province, so she recalled growing up eating red-cooked meats in her book, “The Seventh Daughter.” These meats are braised in soy sauce, wine, spices and sugar, and the pork belly version is particularly rich, wobbly with fat and slick with a glossy glaze. Bauer wrote that this was one of the Mandarin’s most popular dishes at a time when pork belly wasn’t favored — but it was a favorite of culinary legend James Beard.

Where to find a great version now: Hunanese restaurants make a similar dish, often named after Chairman Mao. Find a homey version at Wojia Hunan Cuisine (917 San Pablo Ave., Albany) and a more elegant, glistening rendition at Easterly (locations in Berkeley, Cupertino, Millbrae and Santa Clara). While it’s not currently on the menu at China Live (644 Broadway, San Francisco), the restaurant has served a great red-cooked pork in the past, so it’s worth keeping an eye on.

Hot and sour soup: Before Chiang opened the Mandarin, she was tired of seeing the same egg drop soup at every Chinese restaurant in San Francisco. So she put hot and sour soup on her menu, and it’s now ubiquitous at Chinese restaurants of all stripes. Hot and sour soup gets its namesake balance from chile peppers or white pepper and vinegar, and it’s typically laced with silky tofu and chewy wood ear mushrooms.

Where to find a great version now: Handmade noodle specialist Shandong (328 10th St., Oakland) makes a lovely classic version teeming with tofu and white pepper. While the soup isn’t currently on the menu at Mister Jiu’s (28 Waverly Place, San Francisco), it’s worth seeking out whenever it returns for its complex depth of flavor.

Peking duck: Chiang helped introduce the Beijing classic to San Francisco, disarming diners with thin, crispy duck skin served with whisps of meat, pancakes and hoisin. Usually a chef carves the duck tableside for an elegant flourish, though that’s not currently allowed under the state’s coronavirus safety guidelines.

Where to find a great version now: Head to Great China (2190 Bancroft Way, Berkeley) for the most acclaimed Peking duck in the Bay Area — shatteringly crisp skin, velvety meat and thin pancakes.

Twice-cooked pork: This Sichuan dish once served at the Mandarin sees pork belly simmered, thinly sliced and then stir-fried in a hot wok so it’s crispy yet fatty and tender. The pork then gets tossed with fermented bean paste, garlic, leeks and vegetables.

Where to find a great version now: Great China (2190 Bancroft Way, Berkeley) is another good bet here. The restaurant’s savory-spicy version uses both pork belly and pork shoulder, and gets extra texture from mushrooms and dried tofu.

Kung pao chicken: Now adopted into the Americanized Chinese food canon, kung pao chicken was a tough-to-find dish in the U.S. before Chiang served it at the Mandarin. The stir-dried dish hails from the Sichuan Province, and features cubed chicken dressed in Shaoxing wine with crunchy peanuts and heaps of dried red chiles.

Where to find a great version now: Mamahuhu (517 Clement St., San Francisco) serves an affectionate Chinese-American rendition that benefits from free-range chicken, crunchy bell peppers, smoked tofu and tingly, Sichuan peppercorn-spiked peanuts.

Sizzling rice soup: Crispy rice and a light, clear broth meet at the last second for this soup’s characteristic sizzling sound. The flavor is typically restrained so diners can appreciate the toasty flavor of the rice.

Where to find a great version now: Hunan Home’s Restaurant (622 Jackson St., San Francisco) serves a traditional sizzling rice soup loaded up with chicken and shrimp. House of Nanking (919 Kearny St., San Francisco) makes a more murky, lemony version that sets it apart from many others in Chinatown.

Janelle Bitker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: janelle.bitker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @janellebitker

"eat" - Google News

October 30, 2020 at 03:57AM

https://ift.tt/3mEKNmR

8 Chinese foods Cecilia Chiang helped popularize — and where to eat them now - San Francisco Chronicle

"eat" - Google News

https://ift.tt/33WjFpI

https://ift.tt/2VWmZ3q

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "8 Chinese foods Cecilia Chiang helped popularize — and where to eat them now - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment